-Phyll Mendacino passed away at age 65 due to COVID-19 complications

By Jill-Marie Gavin for the CUJ

The last time Red Lodge Transition Services (Red Lodge) organized a large event at Two Rivers Correctional Facility (Two Rivers) was in August of 2019.

On August 31, 2019, inmates and visitors gathered for the annual “prison pow wow.” Throughout the whole event, laughter rang out across the yard and the big drum thumped in the background. Misting tents cooled off family and guests of inmates while everyone ate, visited and danced with their loved ones.

Red Lodge, a non profit organization that helps Indigenous inmates remain in contact with family, get on their feet once released and hopefully keep from reoffending, organized that pow wow for Two Rivers. Red Lodge travels to all the Oregon prisons annually to support Native American Religious Freedoms. They also held a smaller event in November of 2019 but have not been able to see any of the inmates since then.

The group returned to Two Rivers for the first time in more than a year on February 13, 2021.

February’s trip to the prison was a much colder and more somber event than in years past.

In March of 2020, Oregon prisons shut their doors to visitors. This closure, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, also ceased all the Native American Religious Services for inmates.

Red Lodge Executive Director Trish Jordan said she felt it was time to resume services for incarcerated Indigenous people.

After Jordan received news of one of their most dedicated volunteers passing away, due to complications of COVID, she began to pursue a plan to bring prayer to the prisons.

“It was easier than I thought it would be. I approached Chaplain Cardona (Two Rivers) first and said we would like to go to all the prisons and pray for the inmates,” Jordan said.

She spoke first to the Chaplain and then was routed through the superintendent’s office.

She told the superintendent, “Even though we can’t go in I know we can change the energy, because we know that’s possible through our prayers.”

The superintendent, Jordan said, was very supportive of the plan.

An area was designated for the group to gather and pray for the inmates from afar.

Before the event took place , there was a historic snowstorm that shut down Eastern Oregon. The space planned for the ceremony was no longer an option but volunteers and family members remained dedicated to the service and arrived to pray in the snow.

This particular reopening of ceremony was a priority for Red Lodge because it was planned to say goodbye to one of their longtime inmate volunteers and dear friend.

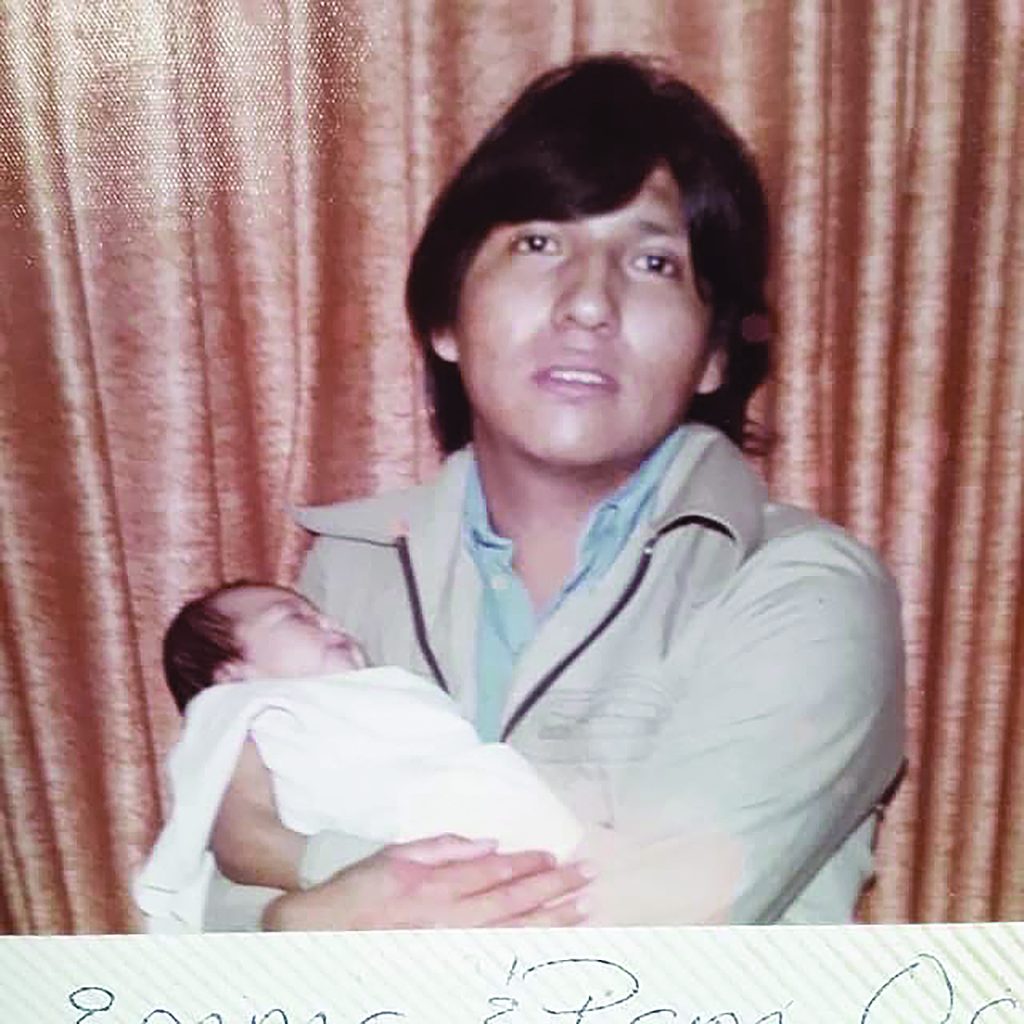

Phyll Mendacino, known as Phillip Red Woman, had been fighting for Native American Religious Freedom rights since he first entered prison in 1998.

Mendacino, age 65, passed away January 26 at Trios Health in Kennewick, Wash. due to complications from COVID. He was enrolled Northern Cheyenne.

Outside of the prison fences and across the field from the main prison, volunteers gathered and began their service by smudging one another.

Mendacino’s daughter, Pamela Steffy, travelled from Kamiah, ID the day before the event to say goodbye to her father.

Steffy said she was a young girl when her father began his sentence of 25 years after he was convicted of murder.

She said her father and mother separated when she was very young but she remained in contact with Mendacino throughout the entire 23 years he served.

Steffy was shocked when she received news he had passed. She then had to break the news to her children who had also become very close to her father.

After weeks of no news from her father she began to think he had gotten himself in trouble but still waited for his call. She continued to ask her children week after week, “Still no grandpa?”

The family had grown accustomed to his weekly calls. Conversations had shifted over the years as he inched closer to release.

Their previous discussions focused on the past slowly turned towards the future. Steffy said her father always asked about Kamiah and Lame Deer, Montana and how they compared to how he remembered them. After he started getting closer to his grandchildren his questions started focusing on current events and what to expect on the outside.

“It was like they breathed more and more life into him and gave him more of a reason for him to go on,” Steffy recalled.

Before the calls ended and as the pandemic worsened his attention and conversations began to revolve around safety.

Mendacino started getting himself in trouble, he told Steffy. As Covid cases began to ravage Two Rivers staff and inmate population, Mendacino expressed his fear of getting it and urged his grandchildren to remain cognizant of their hygiene and to wear masks whenever possible.

To date, Two Rivers Correctional Facility has had the highest number of Covid cases in the state. Mendacino was one of 13 deaths at the Umatilla prison in January.

When her father did pass Steffy didn’t receive word from the prison, but rather through Facebook.

Jordan messaged Steffy and let her know that prison was trying to reach her as next of kin.

“It blew me away because he was so scared of getting Covid. He would call and tell me people are getting Covid pardons. He was hoping to get out because he has had so many appeals and fought to get out for so many years,” she said.

With the help of Jordan, the family set a date to say goodbye to Mendacino. They prepared to travel to Umatilla for closure.

Steffy and her family weren’t the only travelers who braved hundreds of miles to attend the service.

Red Lodge volunteers drove from as far as Klamath Falls. A table was set up with photos of Mendacino and the group lined up across the snowy field that hosted the sunny pow wow less than two years earlier.

The windows were dark and the inmates were not allowed to come out to hear the songs but the group sang on.

Michael Ray Johnson, General Council Vice Chair for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, opened the ceremony with the Washat bell.

Each member of the family shared their words in bidding their relative farewell before Mendacino’s obituary was read.

Volunteers all spoke about Mendacino’s decades of work to liberate Indigenous inmates and to make a way for true religious freedom.

Chaplain Cardona also became emotional as he talked about the inmate’s passion for spirituality.

Steffy said of her father, “His faith was what held him closest to Native culture. He always wanted to share that. He was always proud of their sweats and their pow wows.”

Steffy was happy Mendacino was able to share his deep cultural knowledge with her children before he left this earth. She said no matter what cultural background someone had, he always wanted to share the ways of his People because he truly believed they helped heal.

She was thankful for the chance to say goodbye in a way he would have liked.

The group stood out in the mid-20-degree weather to sing and pray, not only for the departed, but for all the inmates who, Jordan said, are on the inside hurting.

Jordan said this won’t be the only service of its kind. Unfortunately, Mendacino has not been the only Indigenous inmate in Oregon to pass away due to COVID.

According to the Center for Disease Control, Native Americans die at a rate twice as high as white Americans. The dangers for Indigenous people in terms of COVID mortality, coupled with over representation in prison populations has made the Indigenous inmate mortality rate a concerning development for Jordan.

Native Americans also have an incarceration rate twice that of White Oregonians according to a 2017 study conducted by the Vera Institute of Justice.

These concerns were heightened during the two week blackout at Two Rivers in December. All these circumstances created a sense of urgency for Jordan to get the ball rolling on prayer events outside all of the Oregon prisons.

Though visitation is still not allowed, she said they must show up for the inmates to send good energy “over the walls.”

“Our religion isn’t written down. We can’t just turn the pages in the bible and minister to ourselves. The way that we practice is very different than Christianity and other religions. It’s an earth-based religion and it requires community. We need to sit at the drum and sing in one heartbeat of the People. Almost everything we do is in community. To not be able to smudge, to not be able to sweat is huge, because Christian groups can send in a DVD of services and we can’t do that,” Jordan said.

Mendacino, Jordan said, understood the importance of their work.

“Phil was an OG. There’s not alot of people who have ever done that much time and he never gave up. He was always fighting for more cultural programming and religious freedom issues. He was always on them about that. He left a big footprint and he will be missed,” Jordan said.

The group of volunteers closed out their service by holding a dinner of First Foods and a small give away in the administrative building.

Mendacino’s body has not been released to the family, but Steffy said when it is she plans to take him home.

“He was very proud of the fact that they started implementing the sweat house and he opened it to anyone, not just Native Americans. He had the desire for belief and was one of the first ones, being there so long, that advocated for their Native culture and Native rights. If he could help other Natives in there, he would. He supported them getting in touch with what he knew and could share. He alway talked about the Peyote services and sacred Medicine Hat beliefs handed down from his grandparents. He shared his family’s ways from Lame Deer with others. It was a good thing and he may have changed some young person’s life. I’d like to take him back home to Lame Deer and bury him alongside all his brothers,” Steffy said.